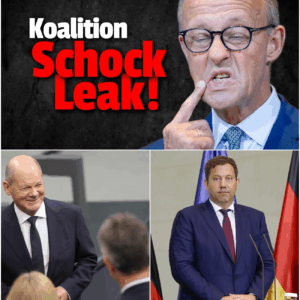

Das Haushaltsdilemma: Warum Kanzler März die Regierung nicht sprengen darf und die SPD mit einem perfiden „Scholz-Trick“ Neuwahlen provoziert Das politische Berlin befindet…

50 Tage, die alles veränderten: Ben Zucker bricht mit seiner Vergangenheit und enthüllt den wahren Grund für seine emotionale Rückkehr nach Berlin Ben…

Der unerträgliche Preis des Ruhms: Als Matriarchin der berühmtesten Großfamilie Deutschlands schien Silvia Wollny unzerstörbar. Doch hinter den Kulissen kämpft sie einen Kampf,…

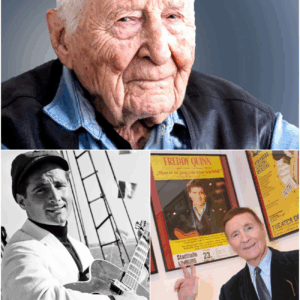

Die Stille Trauer des Show-Giganten: Freddy Quinns verborgene Tränen und das Vermächtnis, das seine Frau Rosy zum Weinen brachte Freddy Quinn, eine der…

Bill Kaultz: Der Tokio-Hotel-Sänger hat Angst vor den Folgen einer Vollnarkose. (Quelle: IMAGO/Reynaud Julien/APS-Medias/ABACA) Bill Kaulitz muss ins Krankenhaus. Der Musiker spricht offen über…

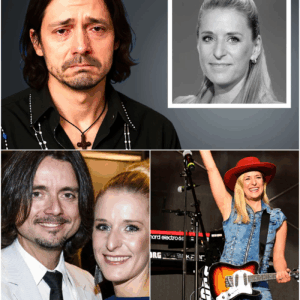

Stefanie Hertels Großer Schmerz: Ex-Mann schockt mit Geständnis über „Quälerei“-Ehe Berlin/Traunstein – Stefanie Hertel, eine der strahlendsten und vielseitigsten Ikonen des Schlagers, ist…

Ein grauer Himmel über Stuttgart und das Ende einer Ära Es war ein Tag, der in die kollektive Erinnerung des deutschen Showbusiness als…

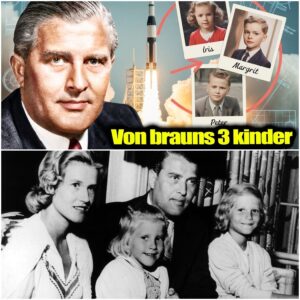

Wernher von Braun, der unbestrittene „Vater des amerikanischen Raketenprogramms“, ist eine jener legendären Figuren der Geschichte, deren Vermächtnis untrennbar mit Kontroverse und Triumph…

Im Alter von 82 Jahren gesteht Lena Valaitis, was wir alle schon vermutet haben: Die späte Liebe rettete ihr Leben nach dem Tod…