Following the first poison gas attack by German forces at Ypres in 1915, gas masks became vital equipment for Allied forces during World War I.

By Peter Suciu

With World War I in a seeming stalemate, German forces in late April 1915 introduced a horrific new weapon to the fighting. In a conflict that already was infamous for reaching new depths in the shameful chronicle of man’s inhumanity to man, the new weapon proved to be so heinous that it was never used again on such a massive scale. It was poison gas. For soldiers on both sides, the horrific effects of the new weapon added another vital piece of equipment to the soldiers’ needs—the gas mask.

While the first widespread use of poison gas occurred on April 22, 1915, near Ypres, Belgium, there had been previous small experiments by the Germans in the weeks prior to the attack. But it was that calm April day that marked how truly devious gas could be as a weapon of war. And while the gas actually killed very few combatants when compared to the vast numbers who gave their lives in the war (according to some sources, as many as 93 percent of gas casualties returned to duty within a few weeks), it was quite a success as a psychological weapon.

The first chlorine gas attack, which hit French Colonial and Canadian troops, appeared as a yellowish-green cloud. When inhaled, the gas destroyed the alveoli of the lungs, causing men to essentially “drown” on the liquid created by their own bodies. This attack caused an immediate panic leading to a massive retreat. So devastating was the attack that it almost enabled a rare German breakthrough. As a result, Allied forces struggled to find effective countermeasures. Early gas masks were nothing more than cotton wool pads or cloth soaked in water or in some cases urine. But, interestingly, they were not the first true gas masks.

As far back as ancient times, the Greeks used sponges as masks to protect the wearer from smoke and other hazardous fumes, both on and off the battlefield. Much later, in the 19th century, American mining engineer Lewis Haslett invented a device that filtered dust from the air. This evolved over the next half century into devices used by miners and for tunneling. However, gas mask protection went into full gear following the German attack at Ypres.

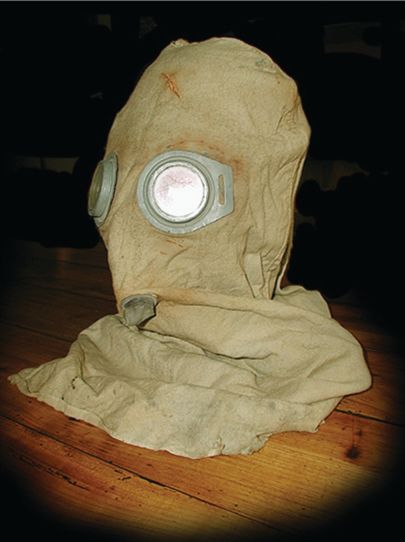

Both the British and French looked to devise new ways of protecting soldiers against the sinister new form of attack. The basic cloth and cotton pads evolved into strips of chemically soaked fabric called the black veil respirator. The next step was to develop a hood worn completely over the head. Designed by Captain Cluny Macpherson, a medical officer to the Newfoundland Regiment, the hood featured a single-windowed visor to allow the user to see. This was unofficially known the Hypo helmet, but was officially dubbed the British smoke hood.

Macpherson’s hood was essentially a khaki-colored flannel bag soaked in a solution of glycerin and sodium thiosulphate—thus. a hypo solution. It was meant to protect against chlorine directly and thus couldn’t protect against other gases, notably phosgene, which was developed by the Germans over the summer of 1915 and proved far more powerful than chlorine while being relatively difficult to detect.

The PH, or smoke hood, was basically a large hood worn over the head, typical of early gas mask technology.

The PH, or smoke hood, was basically a large hood worn over the head, typical of early gas mask technology.

For this gas, the British developed the P helmet, also known as the PHG or PH helmet. It was officially designated the tube helmet since it had an exhalation valve for the user’s mouth. It was still basically a bag that was worn over the head, but it featured two mica eyepieces to allow users to see, a 50 percent increase over the hooded mask. The new version also offered improved chemical impregnation, but it was still a dreadful solution, made worse because the impregnating solution sometimes was so thickly applied that it made a sticky mess.

The dubious hood was finally superseded by the main British gas mask of World War I, the small box respirator (SBR). Interestingly, the first version was known as the large box respirator (LBR), but it proved to be too bulky, as it needed a box canister to be carried on the back. However, the LBR’s development led to the SBR, which featured a single-piece, close-fitting rubberized mask with eyepieces. The box filter was actually worn around the neck in a canvas carrying bag. The system offered an additional benefit: the SBR could be upgraded as more effective filter technology was introduced. The LBRs were produced in large numbers and were issued to rear-guard troops and artillery personnel. Several million SBRs were produced, and many have survived, making them popular with collectors.

One form of gas was so deadly that no gas mask was truly effective. This was mustard gas, which caused severe damage simply by making contact with the skin. No successful or effective countermeasure was found during the war. The Scottish Highland regiments were especially vulnerable since they were still wearing kilts in the trenches. At various points the troops actually took to wearing women’s tights as a form of protection.

The French first used protective goggles and a filter over the mouth. The results were not particularly effective; the gas could easily penetrate the goggles, causing serious eye irritation. By October 1915, it was reported that some 100 different devices had been tested. Eventually a single solution was found; it would become the M-2 gas mask. This consisted of an all-in-one unit that featured a chemically impregnated pad made up of many layers, along with a built-in eyepiece. The first model was made in only a single size and featured a single panoramic eyepiece made of cellophane. The subsequent second model, also confusingly known as the M-2, incorporated two circular eyepieces that were double-layered, with an outer glass layer along with an inner cellophane layer. Soon after its introduction, a design flaw was discovered with the second model of the M-2. After a half hour of wear, the eyepieces could fog over. The glass layer was eventually removed altogether, making for yet another variation that is encountered today.

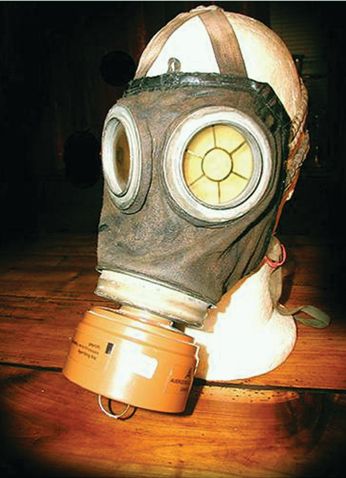

The main German gas mask of World War I featured a rubberized fabric mask with eye pieces and a separate cylindrical screw-fit filter.

The main German gas mask of World War I featured a rubberized fabric mask with eye pieces and a separate cylindrical screw-fit filter.

In all, more than 29 million M-2 gas masks were issued and used by French, American, Italian, and Belgian forces. However, the American forces tended to use the M-2 as a backup gas mask while relying on the SBR for primary use. Later in the war, General Order 78 went so far as to forbid the M-2 from use except for those who had head wounds or could not otherwise wear the SBR.

Today, finding an M-2 can be quite a challenge. While produced in large numbers, the materials used and the arduous conditions on the battlefield meant that very few survived. Thus, examples in good condition can range in price from several hundred to several thousand dollars.

Among the rarest masks from World War I is the Italian Polivalente mask, which was similar in design to the French M-2. World War I collector Gus Bryngelson says the mask, which also featured a cloth face cover with lenses, needed to be moistened to work. “You did not need to urinate on it to make it work,” says Bryngelson, “I suppose that it is possible that there could have been examples of soldiers doing so if there was no source of water, but I doubt it as the front lines were always a very wet place.”

The M-2 was not the only French gas mask used during the war. The French actually took a cue from the Germans. By the fall of 1915, the Allies were also using poison gas, and the Germans were quick to adapt with the Lederschutzmaske 1917, which featured a rubberized fabric mask with eyepieces and a separate cylindrical screw-fit filter that could be changed once its filling become ineffective. This mask was produced in three sizes and was initially carried in a cloth bag.

The French essentially copied the German pattern in the ARS 17 mask of 1918, and these remained in service until the end of the war. “The French Army used the ARS 17 mask up to 1935,” explains advanced gas mask collector Boris Plotnikoff, who has collected the items for nearly 45 years. He says the ARS 17 was used extensively in the interwar period and was only replaced by the ANP T 31 in 1935. However, the French produced the ARS 17 right up to the outbreak of the World War II, thus making it possible to find original versions—albeit post-World War I models—in fine condition.

The British Small Box Respirator was the main gas mask used by the British on the Western Front.

The British Small Box Respirator was the main gas mask used by the British on the Western Front.

As collectibles, gas masks have never been as desirable as the helmets, firearms, and uniforms, but as the 100th anniversary of the War to End All Wars nears, prices for all things from the conflict are on the rise, including gas masks. Surprisingly, other than the rare M-2, the gas masks have endured the passage of time very well, says advanced collector of headgear Roger Lucy. “The price of gas masks in general is stable or if anything falling,” says Lucy, who stresses that demand for World War I gas masks is relatively light.

Bryngelson says collectors today face a “no-man’s-land style mine field. There have been many masks offered on the online auction sites that have been misrepresented, but mostly due to the ignorance of the sellers.” Bryngelson says that he has seen every type of gas mask ever produced being represented as an original World War I mask, “but there are few of the later ones that will pass as wartime examples to a knowledgeable collector.”

Most experienced collectors note that while some World War I gas masks are still available, most are already in collections. Bryngelson observes that World War I gas masks shouldn’t be considered all that rare, simply because so many came home with returning doughboys. “The German masks were a favorite souvenir of U.S. and Commonwealth soldiers,” he says, adding that the German masks often had company. “U.S. soldiers were also allowed to take their own masks home as well.”

At larger militaria shows, such as the annual Show of Shows in Louisville, there are usually at least a few gas masks offered for sale. Many large dealers own some masks, but the issue for new collectors is how much they are willing to pay. While the Cold War versions of military gas masks regularly show up in surplus catalogs and can be found at Army/Navy shops for under $30, authentic World War I-era masks are far more expensive. “Nowadays, it is hard to find a World War I gas mask at a low price, at least in good condition,” says Plotnikoff. “The prices are also continuing to go up.”

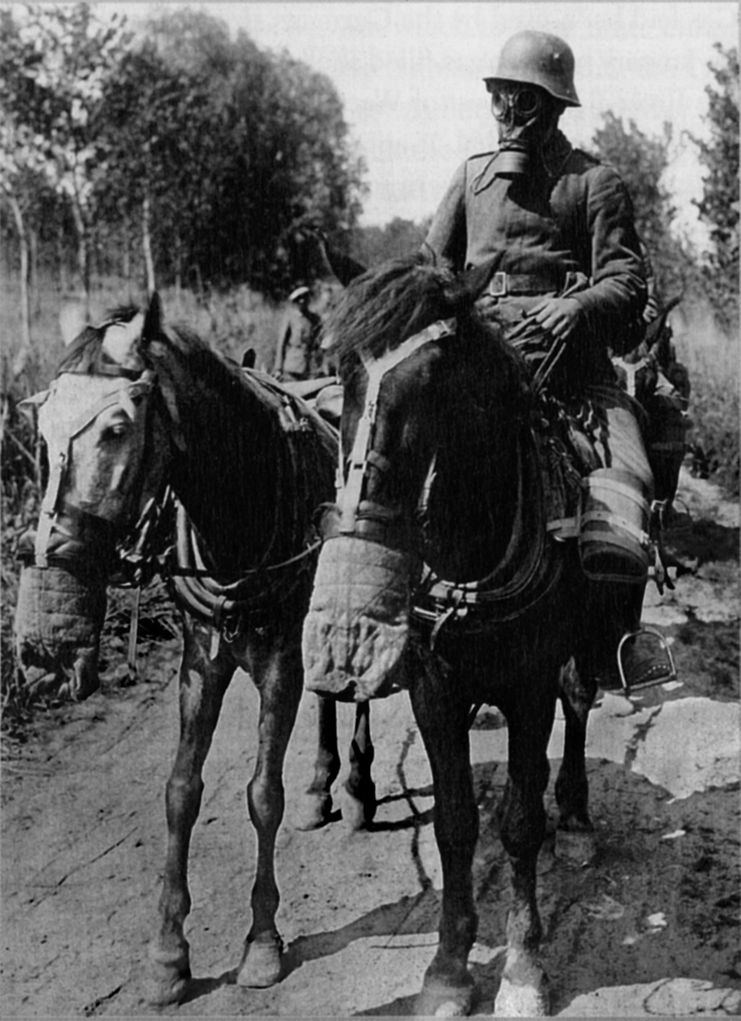

A German soldier and his horses wear gas masks.

A German soldier and his horses wear gas masks.

New collectors may opt to start with the later-period masks, which are in mint condition, says Plotnikoff, and can be had for $10 to $100 according to the model. German masks, however, run as high as $1,000 or more. Many masks are simply not seen often by collectors at all, such as the Russian Zelinski-Kummant mask that featured a rubber head cover or the Austrian version of the German mask. None of these have to date been faked, largely because it would be difficult to fake the age and wear of the rubber. However, new collectors do need to be cautious of replicas, which are made for the reenactor market. These are not offered as original very often, says Bryngelson, who adds, “They are not exactly the same, but look correct.” It isn’t clear whether the replica masks for reenactors technically can be called gas masks since they don’t really work and are more a complex costume item .

A more common concern, Bryngelson says, is that postwar examples of wartime masks can create confusion. “I do have a French ARS 1917 that was made in 1939,” he says, noting that it is the same as a World War I-era mask, “except that it is in very good condition, as the First World War time masks are nearly all hard as a rock, and very difficult to display.”

Once in a collection, the issue for gas mask collectors is their care and preservation. Gas masks can be very fragile; they should be kept out of direct sunlight and the rubberized cloth should not be allowed to dry out from being in too humid or too dry conditions. “As for perseveration, I have not encountered any problems,” says Lucy, “except with a Great War small box respirator whose face piece seemed to be drying out.”

While gas warfare has thankfully been used only a few times since the guns fell silent in November 1918, the history of the horrible conflict lives on in the gas masks that helped protect the wearers. And, although these can’t tell stories, if you look through the glass eyepieces, you can better appreciate what it must have been like to endure the hell of the trenches while wearing the masks and peering anxiously ahead for a telltale cloud of gas.